Discussing sound literacy instruction, supporting teachers and defending public education

Monday, March 29, 2021

The Reading Helper

Monday, March 22, 2021

Reading Aloud for Better Human Understanding: Asian-American Picture Books

Prejudice and hate crimes against Asian-Americans are not new in the United States, unfortunately, but the recent increase in bias related crimes against this segment of the American population reminds us that anti-bias efforts remain critical. The need to address the issues head on is made doubly important when political leaders are among the principal spreaders of this unreasoned hatred. One way to combat prejudice is through knowledge and understanding and one good way to spread knowledge and understanding is through a good book. Here are some great picture books that will help young readers learn about their Asian-American classmates and neighbors.

Long one of my favorite read alouds for children in grades 2-5, Angel Child, Dragon Child, by Michelle Maria Serat, with pictures by Vo-Dinh Mai, tells the story of Ut, recently arrived in the United States from Vietnam. Ut is teased by her new classmates for her different language and different clothes. School is a sad, dispiriting experience and home is a place where she misses her mother who has not made the journey with the family. Ut eventually makes an unlikely friend at school, a boy who was her chief tormentor, and the school community eventually unites around Ut and her family. Wonderful soft pencil and watercolor illustrations enhance the story.

Just published this year, Eyes that Kiss in the Corner, by Joanna Ho, with drawings by Dung Ho, is a powerful reminder of the importance of a positive self-image for all young people. When a young Asian girl notices the difference between her eyes and the eyes of the other children in her class, she draws on the strength of her mother and grandmother to come to an understanding that her eyes are special and beautiful and filled with stories from the past and hope for the future.

An old, much loved favorite is Taro Yashima's Caldecott Honor winning tale of the Crow Boy. Chibi, or "tiny boy", is a strange boy in school. He was afraid of the teacher and could not learn a thing. He was afraid of the other children and could not make friends. The other children in school called him stupid and slowpoke. But day after day, year after year, Chibi came trudging to school. Finally, Chibi finds a teacher who understands him. Mr. Isobe discovers Chibi's special gifts. When Chibi shows off his ability to imitate the sounds of birds, the children are amazed and saddened by how much they had mistreated Chibi all those years. A character and a story to remember, with a universal message.

Monday, March 15, 2021

Henny Penny Discovers Learning Loss

It was a difficult year in the barnyard with all the animals confined to their own homes because of a mysterious and devastating avian flu. Henny Penny, cooped up in her humble abode with a half dozen chicks scurrying about unable to go to school, was at her wits' end. She barricaded herself in the TV room and turned on Foxy News. There she heard a report from an education expert, one Chester Tester, that the entire barnyard was going down the tubes due to an outbreak of "learning loss."

Henny Penny flew into a panic. She flung open the door calling to the chicks, "You are losing learning. You are losing learning. Hurry we must find it." Henny Penny and her chicks scurried around the chicken house looking for their learning. The looked under the beds of straw. They looked in the kitchen. They searched the family room. They even rifled through the medicine cabinet, but they could not find their learning.

Finally, Henny Penny FaceTimed her friend, Ducky Lucky. "Ducky Lucky," said Henny Penny, "I just heard on Foxy News that my chicks are losing their learning."

"Oh, no!" said Ducky Lucky. "If your chicks are losing their learning, mine must be, too. Our friend Goosey Loosey is here, let's see what she thinks."

Goosey Loosey came onto the FaceTime call. Henny Penny said, "The chicks are losing their learning! The chicks are losing their learning!"

Goosey Loosey said, "You know, I haven't seen my chicks carrying their learning around in weeks. I think they must have lost their learning, too. It's a community problem. We need a Zoom meeting with all the animals in the barnyard."

Goosey Loosey, who was the best organized of the three, sent out a Zoom invitation to Turkey Lurkey, Drakey Lakey, Goosey Gander, and Foxy Woxy. At first the Zoom meeting was a disaster with each of the animals clucking at the same time and Goosey Gander having microphone issues, but finally Henny Penny shouted over the din, "Our children are losing their learning! Our children are losing their learning! What can we do?"

Everybody started clucking and cackling again until Foxy Loxy intoned in a deep clear voice, "I can help you."

"What can you do?" the concerned parents all asked at once.

"Well, first we need to measure the learning that has been lost," said Foxy Loxy.

"How do you do that?" they asked.

"Oh, with a great big standardized learning loss test," said the sly fox. "I have one ready to go."

"But what if the test shows they have learning loss?" asked Turkey Lurkey.

"Oh, well then, my den of learned foxes will offer the chicks intensified tutoring and summer school. It really works wonders," enthused the fox.

"That sounds pretty expensive," said Goosey Gander who was always worried about money.

"Oh, no!" said Foxy Loxy slyly, "all you need to do is let my group of foxes into the hen house."

Foxy Loxy smiled and licked his lips. The group of concerned parents murmured to each other in concern for their chicks. They were about to agree, when Drakey Lakey spoke up.

"Wait a minute. Are we sure our children have lost their learning? I know a year away from the schoolhouse is concerning. And I know the online learning is not as good as beak to beak learning, but just what are we worried about here. Our children are learning lots of things. They have learned how to make the best of a bad situation. They have learned how we all need to pitch in to help each other. They have learned to wear masks in public. They have learned a lot about communicable diseases. They may have different learning this year, but is that the same as losing learning? Before we let the foxes into the hen house, we better be sure there is a big problem."

The Zoom meeting went silent. Goosey Loosey shut down Foxy Loxy's Zoom feed. She said, "You know maybe we have bigger things to worry about than learning loss. I am going to go read my chicks a book."

For some serious reading about the silliness of learning loss check out Peter Greene's collection of the best pieces on the topic here.

Monday, March 8, 2021

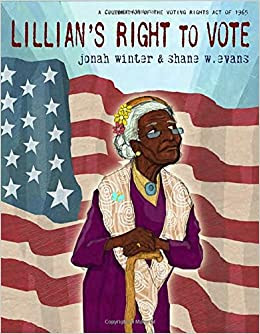

Read Alouds for Social Justice: The Right to Vote and Combatting "The Big Lie"

This past Sunday was the anniversary of "Bloody Sunday," the attack on peaceful protestors on the Edmund Pettis Bridge in Selma, Alabama that resulted in many marchers, including future Congressman John Lewis, being beaten nearly to death. Those marchers were seeking the most basic of American rights, the right to vote. Not long after Selma, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which was supposed to protect everyone's right to vote. Much of that landmark legislation was gutted by the Supreme Court in a 2013 decision, and that action brought on a new round of attempts to suppress voters. The Big Lie propagated by former President Trump and his followers, asserting that the latest presidential election was rigged, has now led to 23 states again trying to limit our voting rights.

Picture books and read alouds have an important role to play in informing children about the importance of voting, the sacrifice others have made so we can vote, and the actions we need to take to make sure that the right to vote is protected. He are some favorites.

For The Teachers March! authors Sandra Neil Wallace and Rich Wallace interviewed the Reverand F. D. Reese, a principal and teacher and a leader of the Voting Rights Movement in Selma , Alabama, along with several other teachers and their families. The interviews make for a compelling story. It is the story of a group of Black teachers who walked off their jobs on January 22, 1965 to march for the right to vote. Charley Palmer's vibrant illustrations bring the story to life.

This biography of Ida B. Wells by one of my favorite authors for young people, Walter Dean Myers, tells the story of the remarkable career of the African American journalist, abolitionist, and feminist who led a powerful anti-lynching campaign and later became involved in the fight for women's suffrage despite the opposition of some of her white suffragist colleagues. Myers' story highlights Ida's courage and persistence, while Bonnie Chritensen's watercolors provide rich historical detail.

Our right to vote is precious. It is never too early to read and learn about how that right has been fought for and defended throughout our history.

Monday, March 1, 2021

Read Aloud Treasures: The Wit and Wisdom of William Steig

Most children these days are well versed in the adventures of Shrek! from the Dreamworks movie franchise and the Broadway musical, but Shrek!, of course, first lived in the very fertile, active, and definitely quirky mind of children's book author and illustrator, William Steig. Steig is a fascinating character himself. He did not write his first children's book until he was in his 60s, but by that time he was world famous as a cartoonist for The New Yorker. His books for children are witty, wacky, wonderful, and slightly off center. Here are some of my favorites for read aloud. Reading these books to children always spurred great follow-up conversations.

Steig's first picture book finds sweet voiced troubadour, Roland, traveling the country to share his songs and stories. A scheming fox named Sebastian fools the trusting Roland and almost roasts him over a fire, until he is rescued by the King. The fox is "put in the dungeon, where he lives the rest of his years on nothing but stale bread, sour grapes and water." Steig establishes his distinctive style with the animals in this story.

Sylvester and the Magic Pebble may be Steig's most famous book. It won the Caldecott Medal for 1970 and shows Steig's mastery of the personified animal cartoon format. Sylvester finds a magic pebble and in a panic makes a foolish wish and turns himself into a rock. After a long time and with growing loneliness, he is finally reunited with his family when his rock form self thinks, "I wish I were my real self again."

The warm and witty story of Doctor DeSoto is a sure crowd pleaser. Dr. DeSoto, the mouse, is a dentist who is careful not to treat "dangerous animals, but one day a fox shows up. Children are delighted to find out how the dentist mouse outfoxes the hungry fox.

Were there ever two more unlikely or more devoted friends than Amos, the mouse, and Boris, the whale? The two friends meet when Amos goes off on an ocean adventure and is rescued by Boris. Soon Boris needs the help of his friend Amos, when he is in danger. Along with Frog and Toad by Arnold Lobel, this is one of the great books about friendship and loyalty you will ever read.

Today would be a good day to share the special pleasures of a William Steig picture book with your students/children.

Monday, February 22, 2021

Joyous Read Alouds: The Books of Audrey and Don Wood

There is a house

A Napping House

Where Everyone is Sleeping

Thus begins one of the great read aloud books of all times, The Napping House, by Audrey Wood, illustrated by her husband, Don Wood. Audrey Wood's parents worked as tent and mural painters for the Ringling Brothers & Barnum and Bailey Circus, which wintered for years near Wood's home in Sarasota, FL. Audrey loved to listen to the stories the circus performers told. When she grew up, she wrote her own stories driven by the tales and cadences she heard from the circus people's stories. The playful use of language is evident everywhere in Wood's stories, which are perfectly matched by the raucous world depicted in Don Wood's illustrations. It is that playful language, plus those large and comic illustrations that make these books perfect read alouds.

An absolutely delightful, cumulative tale of nap time at Granny's house with a snoring Granny, a dreaming child, a dozing dog, a snoozing cat, a slumbering mouse, and one wakeful flea who upsets the quiet repose and causes a huge commotion. The language will have the children tapping their toes and snapping their fingers and the illustrations will induce squeals of laughter. Language Development 101.

This Caldecott Honor Book tells the comical tale of King Bidgood, who would not get out of the tub. He holds battles in the tub, has lunch in the tub, goes fishing in the tub, holds a dance in the tub and no one can stop the madness until the young page pulls the plug. More wonderful repetitive language and the illustrations of goings on in the bathtub are each worth a story in themselves.

This book is sure to resonate for any child who has used a bad word in polite company without really realizing what the word meant or the impact the word would have on the adults in the room. In other words, a book for every child. Elbert's cure is the same as we might have imagined, he gets his mouth washed out with soap, but Elbert finds a more creative way to tame the bad word,-by adding new words to his vocabulary. Delightful tale.

How do you hide a red ripe strawberry from a big hungry bear. Little Mouse tries many ways to hold onto the strawberry. He disguises it, locks it up, buries it, but ultimately determines there is only one way to protect the red, ripe strawberry. Lots of onomatopoeia and huge witty illustrations of the biggest strawberry you have ever seen, make this book a winner for the primary school set.

Monday, February 15, 2021

Reading Aloud with Mem Fox

The Australian Open Tennis tournament is going on right now, and while I watch and root for Serena Williams to defy advancing age and the encroachment of the responsibilities of a full life to win another major title, my reading teacher mind turns my thoughts to the great Australian writer for children, Mem Fox. Mem Fox's books have been a part of my read aloud repertoire ever since I discovered Wilfred Gordon McDonald Partridge back in the mid-1980s. From there it was Hattie and the Fox and what I have come to call her Marsupial Trilogy: Possum Magic, Koala Lou, and Wombat Devine. Eventually, I got to hear Mem Fox speak at an International Reading Association Conference and discovered that not only was she a great author and a charming speaker, she was also a passionate advocate for reading aloud. You can read what she has to say on the subject in her book for parents Reading Magic - How Your Child Can Learn to Read Before School - and other Read-Aloud Miracles.

Here are some of my favorite Mem Fox Read-Alouds.

My personal favorite Mem Fox book, deals charmingly with the very real issue of losing your memory as you grow older. Wilfrid Gordon McDonald Partridge is a bright and adventurous little boy who befriends a woman who lives in the nursing home next door, Miss Nancy Allison Delacourt Cooper, because she has four names just as he does. When Wilfrid discovers that Miss Nancy has lost her memories, he sets out to help her find them. Julie Vivas' vibrant pastel illustrations bring the story to life joyfully.

Wombat's greatest desire is to have apart in the Nativity play during his school's Christmas pageant. The auditions for the show are very nerve wracking for our wombat hero. Will there be a part for him?

The most popular children's book ever in Australia, this is the story of Hush, who has been made invisible through the magic of Grandma Poss. When he wants to see himself again, he and Grandma must travel across Australia to find the magic food that will make him visible. Julie Vivas is back weaving her whimsical magic with the illustrations.

Mem Fox is a magical story teller who has worked with a number of talented illustrators. Her books make great choices for reading aloud whether in the classroom or through Zoom, or especially for a warm and winning bedtime story.

Monday, February 8, 2021

Read Aloud Winners: The Trickster Tales of Gerald McDermott

Everyday is a good day for a read aloud, of course, but some books make better read alouds than others. Among my favorites are the trickster tales as winningly told and exquisitely illustrated by Gerald McDermott. McDermott was not only a world class artist, his illustrations just literally jump off the page at you, but also an expert in folklore. Trickster tales come to us from many different cultures and McDermott mined these rich resources for these entertaining stories.

Perhaps the most familiar of McDermott's books, this Caldecott Honor Book established McDermott's distinctive style. Anansi is a troublemaker whose six sons try to save him from all the problems he causes. A West African Folktale.In this tale from the American Southwest, the animals of the desert teach the troublesome Coyote a lesson.

In this tale from India, a hungry, clever Monkey must find a way to get the tasty mangoes from the island in the river with Crocodile's help, without becoming Crocodile's lunch.

In this Native American tale from the Pacific Northwest, Raven wants to bring light into the world, but first he must find out where Sky Chief keeps it.

In this tale from the Amazon, Jabuti the Tortoise is a fine musician and an irritating trickster. Vulture plots a trick of his own to play on Jabuti on the way to a concert in heaven.

My personal favorite of these trickster tales. Zomo the Rabbit retells the West African tale of a tricky rabbit who is very clever, but not very wise. Will the Sky God help him find wisdom?

Reading several of these titles would make for a great read aloud unit on trickster tales in folklore. What are you reading aloud to your students/children today?

Wednesday, December 16, 2020

A Holiday Gift of Poetry 2020

The holidays will be a bit different for all of this year, but one constant source of joy and solace for me is poetry. Here are a few that I have resonant in this somewhat scary, socially distanced time. Happy Holidays.

One river gives

Its journey to the next.

We give because someone gave to us.

We give because nobody gave to us.

We give because giving has changed us.

We give because giving could have changed us.

We have been better for it,

We have been wounded by it –

Giving has many faces: It is loud and quiet,

Big, though small, diamond in wood-nails.

Its story is old, the plot worn and the pages too,

But we read this book, anyway, over and again:

Giving is, first and every time, hand to hand,

Mine to yours, yours to mine.

You gave me blue and I gave you yellow.

Together we are simple green. You gave me

What you did not have, and I gave you

What I had to give – together, we made

Something greater from the difference.

Wonder and Joy

Robinson Jeffers

The things that one grows tired of -- O, be sure

They are only foolish artificial things!

Can a bird ever tire of having wings?

And I, so long as life and sense endure,

(Or brief be they!) shall nevermore inure

My heart to the recurrence of the springs,

Of gray dawns, the gracious evenings,

The infinite wheeling stars. A wonder pure

Must ever well within me to behold

Venus decline; or great Orion, whose belt

Is studded with three nails of burning gold,

Ascend the winter heaven. Who never felt

This wondering joy may yet be good or great:

But envy him not: he is not fortunate.

Ode to My Socks

Pablo Neruda, translated by Robert Bly

Mara Mori brought me

a pair of socks

which she knitted herself

with her sheepherder's hands,

two socks as soft as rabbits.

I slipped my feet into them

as if they were two cases

knitted with threads of twilight and goatskin,

Violent socks,

my feet were two fish made of wool,

two long sharks

sea blue, shot through

by one golden thread,

two immense blackbirds,

two cannons,

my feet were honored in this way

by these heavenly socks.

They were so handsome for the first time

my feet seemed to me unacceptable

like two decrepit firemen,

firemen unworthy of that woven fire,

of those glowing socks.

Nevertheless, I resisted the sharp temptation

to save them somewhere as schoolboys

keep fireflies,

as learned men collect

sacred texts,

I resisted the mad impulse to put them

in a golden cage and each day give them

birdseed and pieces of pink melon.

Like explorers in the jungle

who hand over the very rare green deer

to the spit and eat it with remorse,

I stretched out my feet and pulled on

the magnificent socks and then my shoes.

The moral of my ode is this:

beauty is twice beauty

and what is good is doubly good

when it is a matter of two socks

made of wool in winter.

Monday, October 26, 2020

Ten Roles of the Instructional Leader in Literacy

I currently teach a graduate course at Rider University for prospective reading specialists. While the course focuses on the theory and research behind sound reading instruction, an underlying goal of the course is to prepare students to be literacy instruction leaders. Toward that end, here are the roles I think a successful instructional leader fills in that critical position. These insights were gained over my several decades long experience as a teacher, reading specialist, supervisor of instruction and director of curriculum.

Listener

One good way to understand what instructional needs a particular teacher or group of teachers has is to listen to them. We all come into these leadership positions with preconceived notions about what good literacy instruction looks like, but in order to lead we must first understand the needs, desires, understandings, and concerns that the teachers have. Sitting down in small groups and with individuals to talk about literacy instruction from the teacher's perspective is a place to start.

Non-Evaluative Observer

The role of leader often involves observations that end with formal evaluations. In order to understand where teachers are in their literacy instruction and what their individual needs might be, however, it is much better to conduct brief non-evaluative observations and follow-up conversations. These observations are always pre-arranged and never formally written-up.

Evaluative Observer

As I said, however, at times the role of the leader involves formal evaluative observations. The goal of these observations, with very few exceptions, should be instructional improvement. To this end, most observations should follow a clinical model, that is, include a pre-observation conference, observation, and post-observation conference. The clinical model helps to insure that the conference is focused on improvement and not some kind of "gotchya" activity. Feedback on lessons should be supportive and aimed at targeted changes. It is better to focus on one or two areas for improvement and to provide clear expectations for implementation, than to overwhelm with a fistful of suggestions.

Sharer

Literacy leaders systematically share their knowledge and the exciting new books and articles that they read in the course of keeping up to date on research and innovation. Professional book discussions, information shares, informative emails, and monthly newsletters are ways that the literacy leader provides updated information for teachers. As a reading specialist, I would hold bi-monthly, pre-school information sharing sessions. As a supervisor, I often conducted before and after school book clubs to look at new books on relevant instructional topics for teachers.

Available Resource

The literacy leader needs to be available to answer teacher's questions about instructional practice or about individual students. Reponses need to be timely and informed by best practice, current research, and actual experience. When the leader is unable to answer a question, she should be able to point to resources that may be helpful and provide those resources whenever possible.

Modeler

Whether it is guided reading instruction, min-lesson development and delivery, book club organization, phonemic awareness instruction, comprehension strategy instruction or any of the many other instructional challenges that may confront the classroom teacher, the literacy leader must be able to model these practices for the teachers through professional development activities and in the regular classroom with the children. Modeling is a powerful way to teach complex concepts to children and adults. The ability to show teachers best practice instruction goes a long way to establishing credibility and trust for the literacy leader.

Resource Provider

When introducing any instructional innovation to teachers, it is critical that the literacy leader provide the teachers with the resources to implement the innovation. When I wanted to implement literature circles in my fifth grade classrooms, I first had to work with building principles to budget money for the books to support the literature circles and then work with the teachers to identify the books that would be used for literature circle study. The same was true for guided reading. Multiple copies of books on a variety of levels were needed to implement the instructional design. Many a good instructional idea fails for lack of resources. If we expect teachers to implement our innovations, we must provide the resources for them to do so.

Advocate

At times the literacy leader must be the advocate for the teacher. This may involve arguing with a principal for a budget line for each teacher to get money to improve their classroom library or sitting in on a parent conference with a teacher whose instruction, grading, or evaluation of a child is being questioned. The role of advocate may also involve providing parent presentations on literacy curriculum and instruction or presentations to the Board of Education regarding curricular decisions.

Program Evaluator

As a literacy leader, you will be inundated with all kinds of literacy programs that promise great things if implemented "with fidelity." The job requires that these programs be evaluated in light of what the current research says is best practice, in light of the needs of the students in the school district, in light of the ease of implementation, and always in light of the fact that teachers teach literacy and not programs. Programs that seek to provide scripted or "teacher proof" instruction eliminate the most critical aspect of any literacy program - the teacher. The implementation of any program must put the teacher at the center and be both grounded in sound research and teacher efficacy. Any program under consideration must come with a commitment to the professional development and the professional expertise of the teacher.

Networker

The literacy leader benefits greatly from a broad network of other professionals filling the same roles. Professional organizations such as the International Literacy Association or the National Council of Teachers of English are very helpful.. Sometimes local universities bring literacy leaders together on a regular basis for information sharing and networking. Sometimes county or regionally based organizations provide the support. No matter where it comes from, it is critical that the literacy leader gain perspective and support from a wide network of people working on the same problems.

I like to think of the literacy leader as the "teachers' teacher." In this role we work to make sure all of the teachers under our supervision are successful, while recognizing that each of them is a unique individual with their own special talents, abilities, and perspectives to bring to the task of literacy instruction.

Monday, October 19, 2020

7 Ways to Help Young Writers

This week I have been reading a new biography of my literary hero, John Steinbeck, Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck by William Souder. In the book Souder quotes Steinbeck's favorite writing teacher, Edith Mirrielees, an English professor at Stanford University, as saying, "Writing can't be taught, but it can be helped." This put me in mind of the work the psycholinguist, Frank Smith, who wrote an article titled, Reading Like a Writer, in which he posited that most of what a writer learns about writing is learned, not through instruction, but through reading in a special way - reading like someone who thinks they are a member of the "writing club."

Of course, even if writing can't really be taught and even if most of what a child learns about writing is learned by reading, there is still plenty of opportunity for the teacher to help, to be the guide on the side. Here are some good ways to help.

- Provide regular opportunities to write on self-selected topics. In order to feel like a member of the writing club, kids need to view writing as a regular part of their lives. Daily writing time puts the developing writer into a perpetual state of rehearsal for writing. For example, because I knew I would be writing this blog entry today, I have been rehearsing, reading, and jotting notes on the topic all week. The expectation of writing something that I want to write means, as Smith says, that I am reading like a writer. That is, my reading is driven in part by my goal of writing about the topic,

- Provide lots of opportunities to read on self-selected topics. If, as Smith says, most of what we learn about how to write comes from reading, it is a given that we must find plenty of time for students to read widely in self-selected topics. We can further help by making the connection between what we read and what we write explicit to the children, perhaps by talking about how certain authors have influenced your own writing or how things that you read about give you ideas for writing.

- Model the process of writing through writing for the students. We know from the research that writers follow a definite process when they write. When we write for students. we not only get to model the process of writing, but we get to share something of ourselves. Talking aloud while we write, which takes some practice, provides the students with a template for their own writing process.

- Model good writing through mentor texts. Much of early writing is imitation. Actual authors provide a template on which we can try out our own efforts to express things in new and attention getting ways. I remember in high school much of my writing was juvenile attempts at satire. I would enjoy writing comic takes on Benjamin Franklin's kite flying experiments or the courtship of Miles Standish, John Alden, and Priscilla Mullins. A teacher happened to mention that my writing reminded her of the books of Richard Armour. Intrigued, I went to the library and took out two Armour books, 1066 and All That and It All Started with Columbus, two riotous historical satires. Armour became my mentor for the silly, hyperbolic, gently reproachful satires I wrote for the next several years. Pointing students to the right books to help them write about their own topics is an excellent way to be helpful. We can then let the professional authors, provide the teaching.

- Provide timely mini-lessons Mini-lessons are a great structure for the teacher to provide a high amount of input into student writing. The best mini-lessons, I think, are those that are most timely. We need to ask ourselves, "What lesson will have the most impact right now?" It makes no sense to teach a mini-lesson on punctuating dialogue until students have begun to try to use dialogue in their writing. Likewise, the best time for a minilesson on varying sentence length is when students are showing that they are capable of writing longer sentences, but have not mastered how to effectively use sentence variety in a composition. It is also important to provide a variety of mini-lessons. We should be providing as many mini-lessons on the qualities of good writing (like show, don't tell) as we are on correct usage and punctuation.

- Conduct writing conferences where you listen, respond, and extend. I like to go to early in the writing process conferences without a pencil in my hand. In these conferences, I want to focus on the writing, what is the writer trying to communicate, how successful are they being, what assistance do they want? To this purpose, I want the writer to do most of the talking and I want my probing questions to elicit more talk to help the writer clarify in their own mind what they are trying to do. I also want to respond personally to the writing, by indicating, yes, this is something I am interested in or this is like something that happened to me, or I can see why this is important to you. Finally, I want to ask some questions that might get the writer to rethink, do further research, or examine what they have done so far. Have you considered...? What if... I was wondering...? The writer should go away from a conference feeling that they are doing work that the teacher values and that they have some ideas to work on to improve their draft.

- Target those things you want to correct Because we are working with students, we should not expect the work to be perfect. Our focus for final revision and editing should be on targeted corrections. What should we target? One focus would be on topics of recent mini-lessons. If the class has been working on varying sentence length, that might be a target. Another focus would be particular challenges that this individual student exhibits. If the student has a tendency to misspell certain words, that could be a target for that individual student. If we try to fix everything, we may cause confusion and frustration. Targeting our corrections means that students can focus on one or two things that will improve the writing, while other problems can be reserved for another writing project.

Monday, October 12, 2020

Haiku: A Path to Poetry for Young Writers

Most young children love poetry, but when it comes to writing poetry they are often overwhelmed by the demands of rhythm and rhyme. Sense suffers as kids scramble for rhyming words.

My Mom

I love my mom oh so much

I love her more than chocolate - Dutch!

She s me all the things I need

And I help her to weed.

Now this poem, written by a second grader, is not without its charms, but it contains a mixture of the profound and the mundane that is typical of a child stuck in the rhyme versus sense conundrum. Freeing children from the demands of rhyme allows them to tap into the natural poetry that is within them. Haiku provides a structured, but non-rhyming. poetic form with which nearly all children can be successful.

Haiku is, of course, the short poetry form that originated in Japan. Literally translated haiku means "beginning poem" and indeed these little poems are an excellent starting point for young poets.

Haiku attempts to capture a single moment or single image in the world of nature. A good haiku should capture an image in the way that a photograph freezes time. As the poet X. J. Kennedy says, "You just point to something and let it make the reader feel something, too."

Haiku consists of three lines containing seventeen syllables, five-seven-five respectively. Writers and translators of haiku do not adhere strictly to the syllable arrangement, but with young writers I believe the strict form provides a helpful framework. As children become more adept at haiku, the rules can be loosened.

Introducing Children to Haiku

First read lots of haiku to the children. I like to find books that provide illustrations or photographs so that I can show the students the image the author was attempting to capture. I have included a list of suggested books below.

Secondly, lay out the "rules of haiku" for children on an anchor chart. My chart contains the following:

1. Haiku attempts to capture a moment in time in nature.

2. Haiku attempts to help a reader see an image in the mind's eye.

3. Haiku attempts to make the reader feel something (happy, sad, amazed, calm, Ahah!)

4. The first line contains five syllables.

5. The second line contains seven syllables.

6. The third line contains five syllables.

Next, analyze a few haiku from the books you have read to the students. Discuss how the poem captures a moment in time in nature. Have the children clap and count the number of "beats" or syllables. Younger children sometimes have trouble clapping and counting at he same time, so I have them clap while I count.

Now you can brainstorm with the children a list of words that might be found in a haiku and that might be a topic of a haiku. . The children will name many things that can be found in nature. I encourage them to use specific words (not just bird, but cardinal, not tree, but oak.)

You are now ready to model writing a haiku for the children. Using the list of words the children have brainstormed, I talk about the image I am going to try to capture in words. Without worrying too much about the syllable count, I put a tentative first line on the board. I encourage the children to look it over and make suggestions. This gives me the opportunity to show the children how we can manipulate the syllable count by adding or deleting words or choosing a different word with the same meaning. This procedure continues through the next two lines. When the first draft of the haiku is completed, I model revision behavior by reading over the piece and making changes that clarify the message and make the poem conform to the structure of haiku.

Finally it is time to have the children try their own haiku. I stand back and marvel as the classroom fills with the sounds of children clapping out syllables and conferring with each other. Generally I have the children do a rough draft, a revised copy, and an edited copy before they transfer the haiku to art paper and illustrate. Children's haiku can be bound into an impromptu big book for all to read or displayed prominently on a bulletin board.

Your students will no doubt amaze you with their facility for haiku. Here are a few written by my second graders in years past.

In a quiet lake

Where I visit everyday,

I hear the birds sing.

Krystal Tamayo

Blue rain falling down

Landing gentle in my hand.

So cold and so clear.

Jennifer Bergman

Juicy red apples

Sitting in the greenish tree.

All ready for me

Kristy Hajducek

Down the sunny path

Slither, slither goes the snake.

Everybody run!

Anne Marie Schamper

Haiku Books

Atwood, A. (1977) Haiku -Vision. NY: Scribners.

__________. (1973) My Own Rhythm. NY: Scribners.

Cassedy, S. (1992). Red Dragon on My Shoulder. NY: Harper Collins.

Crews, N. and Wright, R. (2018). Seeing Into Tomorrow: Haiku by Richard Wright. Millbrook Press.

Lewis, R. and Keats, E.J. (1965) In a Spring Garden. NY: Dial Books.

Raczka, B. and Reynolds, P. (2018). Guyku: A Year of Haiku for Boys. NY: HMH Books.

Ramirez-Christianson, E. and Gallup, T. (2019). My First Book of Haiku Poems. North Clarendon, VT: Tuttle.

Salas, L. P. (2019). Lion of the Sky: Haiku for All Seasons. Millbrook Press.

Teacher Resources

Donegan, P. (2018). Write Your Own Haiku for Kids: Write Poetry in the Japanese Tradition. North Clarendon, VT.: Tuttle.

Hopkins, L.B. (1998). Pass the Poetry, Please! NY: Harper Trophy.

Kennedy, X.J. and Kennedy, D. (1999) Knock At A Star. Boston: Little Brown.

This post is revised from an article that appeared in The Reading Instruction Journal.

Monday, October 5, 2020

Word Recognition: To what extent is it "self-taught?"

I taught myself how to decode. No, I was not some precocious early reader who intuited how words work at three and was reading before entering school. And, yes, my first grade teacher. Ms. Rickles, did a very creditable job in teaching me the alphabetic principal and the phonological awareness I needed to get myself started on the road to being a reader. Most of what I learned about the ways words work, however, I learned by reading and I can distinctly remember that happening to me.

Early in the second grade, my mother enrolled me in the Weekly Reader Book Club. I was thrilled when the package with my first book arrived with my name on it. The book was a Whitman/Golden Book adaptation of a Disney True Life Adventure documentary series called The Living Desert. The book contained lots to interest a seven-year-old boy and I read it with a vengeance. It was probably a bit above my reading level, but with the help of my understanding of sound/symbol relationships learned in school, a bit of my own background knowledge, the copious pictures in the book, and some determination, I was able to decode words like iguana, rattlesnake, prairie dog, desolate, tortoise, habitat, evaporation and so forth. Along the way, although I was not aware of it at the time, of course, I was teaching myself the orthographic system of our language. The more I read, the stronger, richer, ad deeper this understanding became.

It has been estimated that there are about 88,500 distinct word families in English. Not even the most heroic of teachers could possibly hope to teach developing readers even a fraction of these spelling patterns. How do we explain how successful readers learn all these patterns? Researcher David Share (1995) hypothesized that readers learn these patterns primarily through the process of successful experiences of "phonologically recoding words." Phonological recoding is the process of translating print to sound. According to Share, this process is a "self-teaching process", which enables the reader to acquire the detailed knowledge of the orthographic structure of the language that is needed for successful reading. The more successful encounters the reader has, the more information is available to recognize new words. As Share puts it, "the process of word recognition will depend primarily on the frequency [with] which a child has been exposed to a particular word, together, of course, with the nature and success of item identification." (p. 155).

The implications are pretty clear. Students need to develop a thorough understanding of the alphabetic principal and phonological awareness (syllables, onset/rime, phonemes) and at the same time they need lots of opportunities to read, so that they can apply this growing knowledge to new and novel constructs. Another implication is that much of this reading must be on the independent level, because the key is "successful interactions." Children will not have the opportunity to put this self-teaching to work, if they are struggling with the reading. Some challenges are welcome, as opportunities to apply growing decoding skills, but for the most part children should be reading at volume in independent level texts. One exception to this general rule would be when a student shows a particular interest in a topic and that level of engagement motivates the reader to "work through" some challenging passages.

Another implication is worrisome. If much of word recognition is "self-taught" through wide reading, and if this ability to self-teach is dependent on a high level of phonological awareness, then children who struggle with phonological awareness will struggle to build the orthographic lexicon they need for skilled reading. As Cassano and Dougherty (2018) have observed, this indicates that the Matthew Effect (the rich get richer and the poor get poorer) in literacy can be laid to weakness in phonological awareness and the subsequently fewer opportunities to develop the ability to decode a wide range of orthographic constructs.

Share's insight is, for me, a clear argument for balance in instruction. While most children need instruction that helps them develop phonological awareness, they also need lots of opportunities to apply this learning in real, independent reading situations. Students who struggle to develop the requisite phonological awareness need continued attention to help in developing that awareness, but also continued opportunities to self-teach through successful encounters with independent and instructional level texts under the guidance of the informed teacher.

Works Cited

Cassano, C.M. and Dougherty, S.M. (2018). Pivotal research in early literacy: foundational studies and current practices. NY: Guilford.

Share, D. L. (1995). Phonological recoding and self-teaching: sine qua non of reading acquisition. Cognition, 55, 151-218.

Tuesday, September 29, 2020

When Best Practice Meets Questionable Methods in Literacy Instruction

All of us try to provide best practice instruction to our students. Sometimes, though, in our enthusiasm to provide the children the instruction they need, we end up using some instructional methods that work against our goals. Here are a few things we know work in literacy instruction, some ways we can turn those good practices into unproductive ones, and then some things we can do instead.

Best Practice: Regular Reading - Kids who read a lot tend to get better at reading, so it is a good idea to get kids to read as much as possible.

Questionable Method: Reading Logs - Research has long shown us that external controls have a negative impact on intrinsic motivation. Reading logs, rigidly employed, can turn the pleasurable act of reading into a chore. Other extrinsic motivators like pizza parties and other non-reading related awards should also be avoided.

What to do instead: Trust in the power of books and focus on student engagement in those books. If we want children to read we need to have many books readily available (classroom library), to provide the opportunity to read them (independent reading), to give children some choice in what they read, and to make sure they are able to read them (just right book). We also need to advertise the wonderfulness of books through daily read alouds and weekly book talks.

If we want to reward kids for reading, make the rewards reading related, such as providing extended independent reading time or increased time to talk about their books or an added visit to the library.

Best Practice: Written Response to Reading - Research shows that when children write about what they have read they increase their comprehension by at least 30%., so we should have kids write after reading

Questionable Method: Journals - Reader response journals are a good thing, but like reading logs, they may be viewed by many kids as a chore that kills the joy in reading.

What to do instead: Journals can be an important part of the classroom reading routine, but they should be used sparingly and not as a daily requirement. They are most successful when the teacher spends time modeling what a good journal entry should look like for the children. One journal a week seems adequate. There are many other ways that children can increase their comprehension of what they have read. Some days a simple turn and talk to a partner about your reading should suffice. Drawing illustrations and acting out scenes in what you have read are other ways to respond. Another productive activity is the Stop and Jot, where children employ post-it notes to identify particularly impactful passages in their reading. Stop and Jots make good notes for a possible later journal entry. Like giving students some choice in what they read, giving them some choice in how they respond is a good idea. Variety matters here.

Best Practice: Vocabulary Instruction - A strong and growing vocabulary is critical to a child's ability to comprehend increasingly complex text. It is, therefore, every teacher's responsibility to provide vocabulary instruction.

Questionable Method: Vocabulary Lists: Recognizing the need to teach vocabulary, teachers assign lists of words to be looked-up, put into sentences, and studied for a quiz at the end of the week. Fifty years of research has shown that this form of instruction does not work.

What to do instead: Vocabulary is best learned in context and from a conceptual base. Teachers provide context for learning vocabulary through discussing words during a read aloud, by talking about words in a story children have just read, and by using such concept oriented strategies as semantic maps, List-Group-Label, and concept circles. Here is some guidance on teaching vocabulary from a conceptual base. Here is an example of the List-Group-Label Strategy.

Best Practice: Decoding Instruction - Research shows that in order to read well, children must learn to quickly and efficiently decode novel words as they encounter them. Since this is a critical reading skill, we must teach kids to decode words as they read.

Questionable Method: Over-reliance on the prompt "sound-it-out"- Sounding out is an important skill for readers to have. The ability to match sounds to symbols is critical, but over-reliance or inflexible dependence on "sounding-it-out" is both inefficient and often ineffective.

What to do instead: The definition of decode in The Literacy Dictionary (ILA) is "to analyze spoken or graphic symbols to ascertain their intended meaning" (italics mine). Meaning is at the center of the decoding enterprise. Children must be taught to flexibly approach an unknown word seeking its meaning by using a combination of strategies including sounding-it-out, but also employing meaning clues, syntax clues, onset and rime, and morphological clues to decode a word. You can read more about the role of meaning and flexible strategies for decoding here.

Best Practice: Listening to Students Read Orally: Listening to developing readers read a passage orally is an important diagnostic tool for the teacher. Student miscues in oral reading or lack of fluency in processing provides teachers with critical information for planning instruction.

Questionable Method: Round Robin Reading: Round Robin or Popcorn Reading where children are asked to take turns reading orally is a long discredited instructional practice. It is ineffective in improving reading and potentially embarrassing for vulnerable readers.

What to do instead: Students should only be asked to read orally as individuals in three situations. One is a private diagnostic conference where the child is reading to the teacher and the teacher is taking a running record for diagnostic purposes. The second is in a small group guided reading session where again the child is "whisper reading" to the teacher listening in over the shoulder and prompting to assist in processing the text. Finally, performance activities like reader's theater or radio reading, where students are given ample opportunity to rehearse their parts before reading orally. You can read more about the problems with Round Robin Reading here.

In our efforts to provide students with the best possible instruction it is a good idea to keep our eyes on the big picture and not on the most immediately expedient solution. The eventual impact on learning will be profound.